How Much Sugar Is in a Mango? A Clinical Perspective

The fact that a single medium-sized mango contains approximately 40-46 grams of sugar can understandably cause concern for the health-conscious individual.

However, the complete story of a mango's sugar content—often queried as chow much sugar is in a mango—is far more nuanced than this single figure suggests. To accurately assess its role within a sophisticated wellness and longevity protocol, we must examine its complete metabolic profile.

The Sugar Profile of a Mango

The sugar in a mango is predominantly a blend of fructose and glucose. The critical distinction lies in its delivery mechanism: unlike refined sugars in processed foods, these natural sugars are delivered within a matrix of dietary fiber, vitamins, and potent antioxidants.

This biological context is paramount. The fiber, in particular, functions as a metabolic buffer, moderating the rate at which sugar enters the bloodstream. This modulation is key to preventing the acute blood glucose fluctuations that can impose significant stress on metabolic systems over time.

Mango Sugar Content by Serving Size

For practical application, it is useful to quantify the sugar content by portion. A clear understanding of these amounts is the first step toward precise control over daily intake, a cornerstone of proactive health management.

Mango Sugar Content at a Glance

This reference table outlines the typical sugar content for common mango serving sizes.

Serving SizeApproximate Weight (grams)Total Sugar (grams)1 cup, diced165 g~23 gHalf of a medium mango100-125 g~20-23 gOne whole medium mango200-250 g~40-46 g

This data clearly illustrates the significant impact of portion control.

It is crucial to remember that your body does not process the natural fructose in whole fruit the same way it handles high-fructose corn syrup. The presence of fiber, water, and micronutrients provides a profoundly different metabolic signal.

Both the context and the quantity of consumption are what ultimately determine the metabolic outcome. While an entire mango delivers a substantial sugar load, smaller, well-managed portions may offer notable benefits.

For instance, one study found that participants consuming just 10 grams of freeze-dried mango daily for 12 weeks demonstrated improvements in blood glucose regulation. This serves as a powerful reminder that with fruit, the appropriate dosage can be transformative. You can explore more about these mango nutritional facts and their implications for your health.

Understanding Glycemic Index and Load

Quantifying the sugar content of a mango is only the initial step. For those dedicated to optimizing their metabolic health, the more salient question is: how does the body respond to that sugar? This is where the clinical concepts of Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL) become indispensable tools.

These two metrics provide a much clearer picture than sugar grams alone. The Glycemic Index measures the velocity at which a food's carbohydrates are converted to glucose and enter the bloodstream. A high-GI food elicits a rapid, pronounced spike in blood sugar, while a low-GI food results in a slower, more manageable rise.

Differentiating Speed from Impact

While GI indicates the rate of glucose absorption, it does not account for the total amount of carbohydrate consumed. This is the role of Glycemic Load. GL considers both the GI and the quantity of carbohydrates in a serving to measure the food's total impact on blood sugar. It quantifies not just the speed of the glycemic response, but also its magnitude.

A food can have a high GI but a low GL if consumed in a very small portion. Mango has a moderate GI, typically around 51, which is quite favorable for such a sweet fruit. Its GL for a standard 120-gram serving is approximately 8.

Glycemic Index (GI): Measures how quickly a food elevates blood sugar.

Glycemic Load (GL): Measures the overall impact a serving of food has on blood sugar.

This distinction is clinically critical. For our patients focused on longevity and metabolic wellness, managing Glycemic Load is a more practical and effective strategy than focusing on GI alone. It offers a more accurate reflection of the insulin demand a particular food will place on the body—a key factor in preserving long-term health and vitality.

Applying These Concepts to Your Diet

Understanding GL allows for the strategic integration of mango into a broader nutritional plan. While its sugar content necessitates mindful portioning, its moderate GL indicates that, when consumed correctly, it does not have to trigger a significant metabolic event.

This principle of balancing food choices is a cornerstone of any effective health strategy. To learn more, we invite you to review our clinical perspective on what a varied diet truly means for long-term health. By focusing on the total glycemic impact of your meals, you can enjoy nutrient-rich foods like mango without compromising your wellness objectives.

How Your Body Processes Sugar from Mango

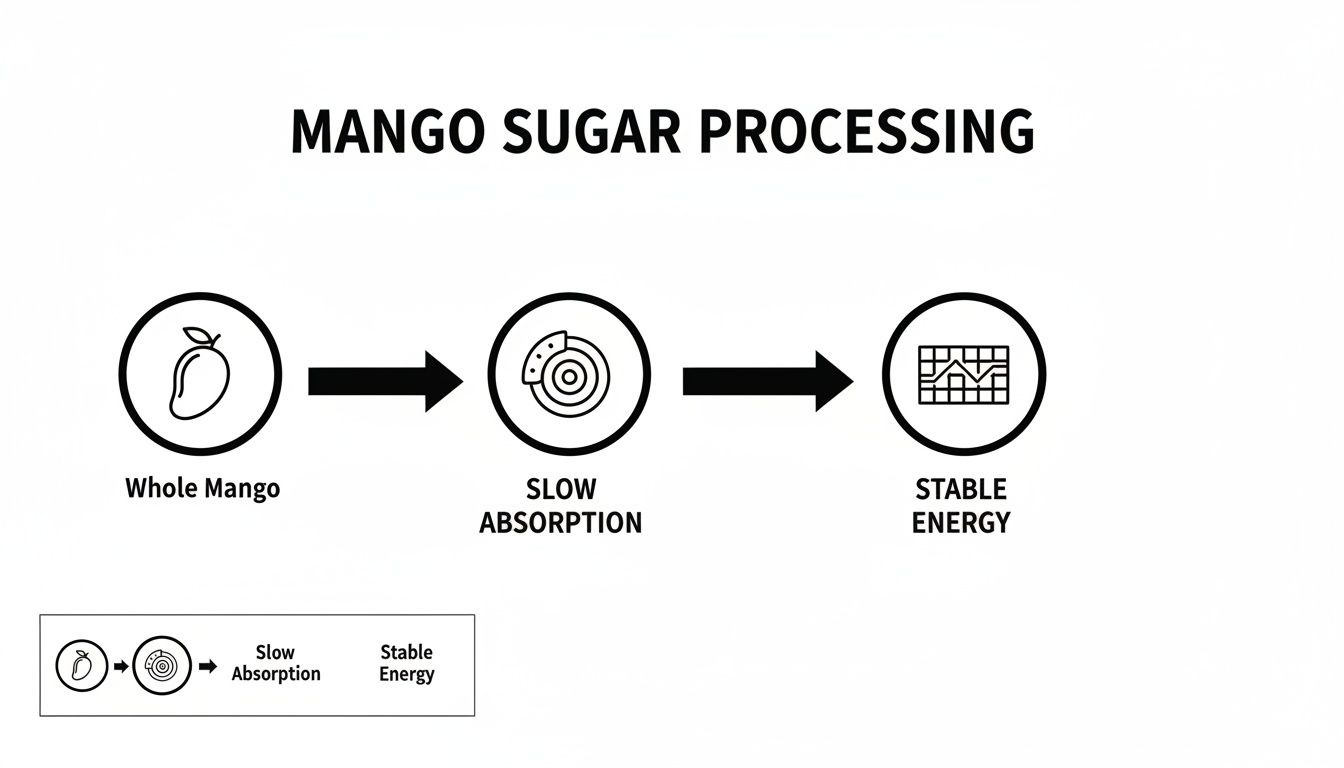

Consuming a ripe mango initiates an elegant biological process. The natural sugars, primarily fructose and glucose, begin their digestive journey, but they do not travel in isolation.

They are intrinsically bound with dietary fiber, a factor that fundamentally alters the body's metabolic response.

This fiber acts as a natural attenuator. Instead of permitting an immediate influx of sugar into the bloodstream, the fiber forms a viscous, gel-like matrix in the digestive tract. This slows gastric emptying and ensures a more gradual release of glucose. It is this measured delivery that prevents the sharp glycemic spikes—and subsequent crashes—associated with processed sweets and sugar-sweetened beverages.

The Whole Fruit Advantage

This mechanism is precisely why a whole fruit elicits a completely different metabolic effect than a processed food with an equivalent sugar content.

A candy bar, for example, delivers what is known as a "naked" sugar load. It is devoid of the fiber, water, and micronutrients that would otherwise buffer its impact. The body absorbs it almost instantaneously, compelling the pancreas to release a large, rapid surge of insulin to clear the glucose from the blood.

In contrast, the sugar from a whole mango is introduced in a much more controlled, manageable fashion. This gradual absorption allows cellular systems to respond efficiently, reducing the overall stress on the pancreas and helping to maintain stable energy levels. This is the essence of the whole fruit advantage—a vital concept for anyone managing insulin sensitivity or pursuing proactive health.

This gentle, fiber-mediated sugar release is a core reason why nutrient-dense whole foods are foundational to any serious longevity and wellness strategy. The goal isn’t to eliminate sugar, but to consume it in its most intelligent, biologically compatible form.

Cellular Impact and Energy Utilization

Once absorbed, the glucose from the mango is transported via the bloodstream to your cells, where it serves as fuel. Muscle tissue can utilize it to replenish glycogen stores, particularly after physical activity, while the brain relies on a steady supply of glucose for optimal cognitive function.

However, the rate and volume of this delivery are of paramount importance.

A slow, steady supply supports consistent cellular function and helps prevent the chronic inflammation and metabolic strain tied to frequent, high-amplitude blood sugar excursions. This controlled process is far less likely to contribute to deleterious processes like glycation, which can accelerate biological aging.

In short, by choosing a whole mango, you are not merely consuming sugar. You are providing your body with a sophisticated, well-managed energy source that works in harmony with your metabolism, not against it.

Comparing Mango to Other Common Fruits

To fully appreciate the metabolic impact of mango, context is essential. Comparing its nutritional profile to that of other common fruits provides a practical framework for making informed dietary choices that align with your health objectives. Not all fruits are created equal in terms of their sugar content and subsequent physiological response.

This analysis is not about categorizing fruits as “good” or “bad,” but rather about understanding their unique properties. For individuals actively managing their metabolic health or fine-tuning their diet for peak performance, these distinctions are powerful. A banana, for example, is often considered a healthy option, yet it contains more sugar and has a greater glycemic impact than an equivalent portion of berries.

The way your body handles the sugar from a whole fruit is completely different from how it processes a candy bar.

As illustrated, the fiber in a whole mango functions as a natural brake, slowing sugar absorption and promoting more stable, sustained energy.

A Clinical Look at Fruit Sugar Content

To put this into perspective, let's compare mango with several other popular fruits. The following table details the sugar content and, more importantly, the glycemic load (GL) for a standard 100-gram serving.

Fruit Sugar and Glycemic Load Comparison (Per 100g Serving)

Comparing the sugar content and glycemic load of mango against other popular fruits to inform dietary choices.

FruitTotal Sugar (grams)Glycemic Index (GI)Glycemic Load (GL)Strawberries4.9g403Watermelon6.2g764Mango13.7g516Apple (Fuji)10.4g386Banana12.2g5111Grapes15.5g5911

These figures precisely position mango within the fruit spectrum. It is certainly sweeter than berries, yet it possesses a more favorable glycemic profile than bananas or grapes, which elicit a more significant blood sugar response per serving.

The key takeaway here is that fruits are not interchangeable. Each one has a unique metabolic signature that can either support or challenge your health goals, depending on how much you eat and how often.

This knowledge enables strategic dietary substitutions. If your blood glucose is particularly sensitive on a given day, you might select strawberries over mango. Conversely, to replenish glycogen stores after intense exercise, a controlled portion of mango can be an excellent choice.

This level of nutritional precision transforms food into a tool for achieving specific biological outcomes. It is a data-driven approach fundamental to any proactive wellness strategy.

Mango's Role in Metabolic Health and Longevity

Understanding the metabolic fate of sugar from mango is the first step. The next is to connect this process to its clinical implications, particularly for patients focused on managing metabolic health or pursuing a longevity-centered lifestyle.

A core objective in optimizing healthspan is the maintenance of metabolic flexibility—the body's capacity to efficiently switch between carbohydrates and fats for fuel without incurring significant physiological stress. Large, frequent glycemic excursions from any source can erode this flexibility over time, challenging insulin sensitivity and compromising cellular health.

This is precisely why portion control is paramount with a fruit like mango. A small, sensible serving can be easily accommodated within a well-structured nutrition plan. A very large portion, conversely, delivers a substantial sugar load that necessitates a powerful insulin response. For individuals with insulin resistance or pre-diabetes, such a demand is particularly taxing.

Glycation and the Aging Process

Persistently elevated blood sugar levels can trigger a damaging process known as glycation. This can be conceptualized as a form of biological "caramelization." When excess sugar molecules circulate in the bloodstream, they can randomly bind to proteins and fats, forming dysfunctional compounds called Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs).

These AGEs are a significant driver of accelerated aging. They cause vital proteins—such as the collagen that maintains skin firmness or the delicate endothelial lining of blood vessels—to become stiff, brittle, and functionally impaired. Over the long term, the accumulation of AGEs is directly correlated with:

- Increased cellular stiffness and a loss of youthful elasticity.

- Greater oxidative stress and the chronic, low-grade inflammation that underlies many diseases.

- Impaired function of tissues and organs throughout the body.

By consciously managing your total sugar intake—including from fruits like mango—you are actively working to minimize the formation of AGEs. This is a powerful and proactive strategy for protecting your cellular health and supporting a longer, healthier life.

An Empowering, Proactive Approach

The connection between sugar, glycation, and aging is not a rationale for fearing fruit. Rather, it underscores the importance of precision and strategy in nutritional choices. The operative question is not merely "how much sugar is in a mango," but how to incorporate it intelligently to harness its benefits without incurring a metabolic cost.

This proactive management is about empowerment, not restriction. For instance, controlling inflammation is another non-negotiable pillar of longevity. You can learn more by exploring a physician's guide to the top 10 anti-inflammatory foods for cellular wellness. By making informed, evidence-based decisions about what you eat, when you eat it, and in what quantities, you can enjoy nutrient-rich foods while actively supporting your long-term metabolic health and vitality.

How to Eat Mango for Optimal Health

Enjoying the flavor of mango without compromising metabolic objectives is entirely achievable with the correct strategy. The goal is not to eliminate this fruit, but to consume it intelligently, utilizing a physician-led approach that harmonizes with your body's biology.

This reframes mango from a potential metabolic challenge to a valuable, nutrient-dense component of your wellness plan. Instead of solely asking how much sugar is in a mango, the focus shifts to how to consume it. A few clear, actionable principles provide precise control over its glycemic impact, ensuring you receive its benefits without the metabolic drawbacks.

The Pairing Principle

One of the most effective tools for metabolic management is the pairing principle. Simply put, one should avoid consuming mango—or any high-sugar fruit—in isolation. Pairing it with other macronutrients creates a metabolic buffer that significantly slows the absorption of its natural sugars.

This simple concept has a profound effect on blunting the glycemic response. Protein, healthy fats, and additional fiber act as a braking system for sugar, promoting a slower, more gradual rise in blood glucose instead of a sharp, insulin-demanding spike.

Combining carbohydrates with protein and healthy fats is a foundational technique for maintaining stable blood sugar and optimal insulin sensitivity. This approach allows you to incorporate a wider variety of whole foods into your diet without metabolic disruption.

The following are effective pairings that apply this principle:

- Protein: Combine diced mango with unsweetened Greek yogurt or cottage cheese.

- Healthy Fats: Add a serving of almonds, walnuts, or chia seeds to your mango.

- Fiber: Blend a small amount of mango into a smoothie with spinach, avocado, and a high-quality protein powder.

Timing and Portion Control

The final components for strategic consumption are timing and portion size. Adhering to a sensible portion of approximately half a cup (about 80 grams) of diced mango is crucial. This amount provides flavor and nutrients without overwhelming the system with sugar.

The timing of consumption also matters. Consuming your mango portion after a workout can be an effective strategy. Post-exercise, muscle cells are more insulin-sensitive and primed to absorb glucose from the bloodstream to replenish their glycogen stores. This timing facilitates the shuttling of the fruit's sugar into muscle for recovery, effectively mitigating a large blood sugar spike.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mango

Navigating the nuances of nutrition invariably raises specific, practical questions. Here, we address some of the most common inquiries our patients have regarding the inclusion of mango in a health-conscious lifestyle, providing the clarity needed for confident dietary choices.

Can I Eat Mango if I Have Diabetes?

Yes, individuals with diabetes can often incorporate mango into their diet, but moderation and strategy are essential. Adhering to a small portion size, such as 1/2 cup (around 80g), is critical to prevent a significant rise in blood glucose.

To further buffer the glycemic response, never consume it alone. Always pair mango with a source of protein or healthy fat, such as a handful of almonds or a serving of plain Greek yogurt. It is also advisable to monitor your blood glucose after consumption to understand your body's unique response and, of course, to consult with your physician to integrate it safely into your meal plan.

Is Dried Mango a Healthy Snack?

Dried mango presents a very different metabolic profile. The dehydration process concentrates the sugar and calories to a remarkable degree. A small handful of dried mango can contain as much sugar as an entire fresh one, making overconsumption very easy.

While dried mango retains some fiber and nutrients, its exceptional sugar density makes fresh or frozen mango the superior choice for anyone focused on metabolic health. If you choose to consume the dried version, it is best treated as a garnish, limiting intake to one or two small pieces.

What Is the Best Time of Day to Eat Mango?

While there is no single "best" time for everyone, consuming mango after a workout can be a prudent choice. Post-exercise, muscles exhibit heightened insulin sensitivity and are prepared to uptake glucose to replenish glycogen stores. This process can help minimize the impact on systemic blood sugar levels.

Conversely, it is generally advisable to avoid consuming large amounts of any fruit on an empty stomach or immediately before sleep, as this can lead to a more pronounced glycemic response. The most reliable strategy for metabolic stability is to pair it with a balanced meal. For more guidance from our physicians on building a healthy diet, please review our article answering your top 10 questions about healthy eating.

At the Longevity Medical Institute, we empower you with the knowledge and personalized strategies to integrate any food into your wellness plan intelligently. Discover our physician-led programs today.

Considering Stem Cell Therapy in San José del Cabo?

San José del Cabo is home to Longevity Medical Institute’s primary regenerative medicine clinic, serving patients seeking physician-guided longevity and regenerative therapies in Mexico.

All treatments are delivered within licensed medical facilities and follow defined clinical protocols. Patients considering care in San José del Cabo are supported through consultation, treatment planning, and follow-up to help ensure clarity, safety, and continuity of care.

Learn more about our San José del Cabo clinic.

Author

Dr. Kirk Sanford, DC — Founder & CEO, Longevity Medical Institute. Dr. Sanford focuses on patient education in regenerative and longevity medicine, translating complex therapies into clear, practical guidance for patients.

Medical Review

Dr. Félix Porras, MD — Medical Director, Longevity Medical Institute. Dr. Porras provides clinical oversight and medical review to help ensure accuracy, safety context, and alignment with current standards of care.

Last Reviewed: October 4, 2025

Short Disclaimer

This information is for educational purposes only and is not medical advice. It does not replace an evaluation by a qualified healthcare professional. For personalized guidance, please schedule a consultation.